A Short History of Green Screen

With the recent release of the Disney+ series, The Mandalorian, we see the next step in green screen technology. It wasn’t unbelievable to see a leap like this with how much technology has advanced within the last ten years. However, since digital effects became the norm in Hollywood, green screen composites evolved much more rapidly than they did in the pre-digital era. So instead of looking towards things that will go with compositing effects, it would be best to see where it all started and appreciate the long road it took to get us where we are today.

The first significant innovation in chroma key technology was the Bi-pack process which Adolf A. Gurtner founded in 1901. Bi-pack is the process of loading two reels of film into a camera so that they both pass through the camera gate together. This process can be used as an in-camera process by loading one reel made of pre-exposed and developed film and an unexposed film strip. Unfortunately, this process was challenging to pull off since it risked jamming the camera.

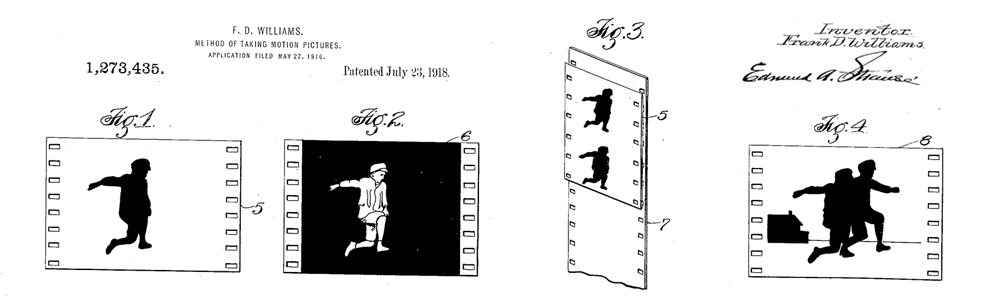

The next significant evolution in matte compositing is the invention of the Williams process in 1912. This invention was able to integrate actors’ movements with previously shot backgrounds. How it worked was that actors would be filmed in front of a black background and printed on high contrast film several times until the holdout matte was created, which would show the black silhouette of the actors on a white background. Then, finally, the original film would be combined to make the final image. This was the only method of using a moving matte at the time. The most notable film that used this process was 1933’s The Invisible Man, which used this method to make the lead actor disappear. The Williams process was highly effective for many years until the Dunning process in 1927.

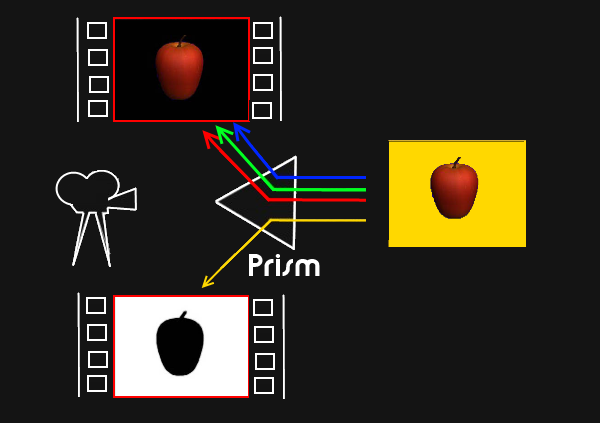

The process is similar to the Williams process but is much more reliant on the color of the background. The background needed to be blue, with yellow lights illuminating the foreground. An optical printer would be used to combine the shot with the desired background. Building on this technique is the creation of the sodium vapor process, which was created in the late 1950s for the Disney film Mary Poppins. The actor would be filmed in front of a white screen lit with powerful sodium vapor lights. The light would glow in a specific narrow color spectrum that falls neatly into a chromatic notch between the various color sensitivity layers of the film so that the odd yellow color does not register on the red, green, or blue layers. This was a highly effective process and won an academy award for best visual effects used in Mary Poppins. Even though this method was highly effective, it was impractical to use for other filmmakers since only one camera was created that could filter out the vapor.

The next significant innovation came with the 1980 film Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back with an LED blue screen. The LED blue screen involves the separation of a narrow slice of blue light from the full spectrum of visible color. Today, we will use a green or blue screen for chroma key compositing because they are the farthest colors from human skin tone. However, this creates an issue if the actor wears any clothing with colors close to the screen; this might create slight transparency. We are still fighting these issues, but with improved compositing software, we can minimize these problems.